http://www.broadwayworld.com/article/JITNEY-Fever-How-One-Play-Secured-August-Wilsons-Legacy-While-Redefining-Race-and-Success-on-Broadway-20170409

Tag Archives: Manhattan Theater Club

Broadway Gets Treated to One More August Wilson Premiere

It comes something as a shock that August Wilson’s Jitney has just now made it to Broadway. The play has a complicated history first premiering in 1982 at the Allegheny Rep and, then after extensive rewrites, at the Pittsburgh Public Theater in 1996. It did not make it to New York until 2000 with a production at Second Stage. Congratulations to the Manhattan Theatre Club for bringing it to the Great White Way.

Though a part of the Pittsburgh Cycle, it is not as fully a realized piece in a socio-political sense as, say, The Piano Lesson (which is perhaps the jewel in the crown of the cycle). Further, the concluding two scenes feel rushed. Nonetheless, the play has many pleasures and shares with Fences a strong foundation of American theatrical realism.

The greatest gift Jitney offers is the final scene of Act One. Wow. Booster (Brandon J. Dirden) has just been released from prison, where he had been incarcerated for murder. After twenty years, there is a reunion between him and his father Becker (John Douglas Thompson). And they go at, tearing into each other, each blaming the other for the death (apparently passive suicide) of Booster’s mother. Recrimination builds upon recrimination. Hurt builds upon hurt. A bitter history of a family is encapsulated in the space of fifteen minutes. Hegel said that tragedy is the opposition of two rights; that is played out here in two great howls of pain. It is brutal, glorious, devastating, honest at the most fundamental human level. It is achieves the heights of O’Neill at his best. (At intermission, I kept flashing back to the Roundabout’s production of A Long Day’s Journey into Night).

Dirden and Thompson give as startling and unvarnished performance as any that can be found on Broadway right now. Other performances captivate as well. André Holland, who did a lot with his few minutes of screen time as Andrew Young in Selma, captures the weariness and hope of Vietnam veteran Youngblood. Michael Potts make the most of the complicated Turnbo – a blowhard, but not without positive qualities – and Keith Randolph Smith invests his Doub with equal measures of humor and wisdom. Director Ruben Santiago-Hudson keeps the direction of the two-hander scenes – the heart and soul of the play – crisp and energized. This was an ensemble cast that listened.

Jitney occupies an unusual place in the cycle as does the 1970’s in African-American history. It is kind of a pause between the Civil Rights Movement (and the decades leading up to that movement) and the paradox of the 1980’s and beyond. The world is shifting beyond the characters are not sure what it is shifting to, and that creates an air of uncertainty for characters and audience alike. The city wants to close down the jitney station for rezoning purposes, but what does this mean exactly. It feels a bit like complaining about Shakespeare’s use of pirates as a deus ex machina in Hamlet, but Wilson himself seems unsure here. Becker’s promise to fight city hall dissipates quickly because of his death due to an industrial accident. The concluding moment where the torch is passed to Booster feels unearned. It is the uncertainty a flaw or a design? It is not clear. Nonetheless, Jitney earns its place in the canon. Like the best American plays, it dramatizes in no uncertain terms the searing pain and heartache of family.

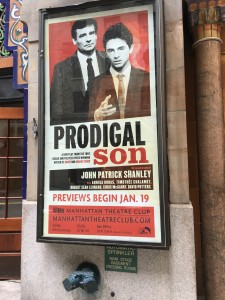

With Prodigal Son, Shanley is Our James Joyce

There comes a moment in James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, when Stephen Dedalus, the author’s alter ego states, “Welcome, O life! I go to encounter for the millionth time the reality of experience and to forge in the smithy of my soul the uncreated conscience of my race.” The novel chronicles how a young man creates himself both as an individual and as an artist. As he authors himself, he walks through the fires large — nationalism, religion — and small — the struggles of adolescence, a dysfunctional family. Last month when I saw Prodigal Son, I came to the conclusion as the lights came up for the curtain call that, at last in John Patrick Shanley, we had our American Joyce.

Much can and has been said about Prodigal Son, but I want to here focus on that Joyce connection. Shanley, as with Joyce, has brought his adolescent self to life through words — through poetry and prose, through philosophy and theology — to be reconsidered, reexamined, to undergo catharsis as much for the audience as no doubt himself. His avatar, Jim, is truly a remarkable creation. And I should add that in Timothée Chalamet (famous for Homeland and Interstellar) Shanley has found the ideal collaborator. Actor and author do not shy away from Jim’s darkness — he says and does the stupid things teenagers often do as they wrestle with the twin tensions of childhood and adulthood — his brilliant narcissism, or his self-destructive impulses. He is not likable the way teenagers on television sit-coms are often likable. But he is engaging and endearing. His darkness is understandable, his pain a source of empathy, his yearning to connect with an world of ideas that he cannot yet quite touch remarkable. The play is no better than when Shanley lets Chalamet tear into a monologue, trip the light fantastic in a way that has the raw magic of stream-of-consciousness to find truths (human truths, perhaps, if not universal truths) in the most Joycean, or given the play’s setting in the 1960’s, Kerouacian way. The actor opens up to show us both the wonder and pain within.

Stanley is at his most powerful when his flawed characters wrestle with faith and doubt (in reference to his perhaps most famous work). What intrigues here for Jim is the same that intrigues for Stephen: the temptation for sin he finds within and not from without. He recognizes the darkness in himself — the darkness that dwells within all of us — but he is intelligent enough (brave enough? foolish enough?) to address it and not ignore it as most do. What will win inside him? Will what Lincoln called “the better angels of our nature” eventually hold sway? Jim does not know. He wants to find the answer, though perhaps it too scares him.

Louise, the headmaster’s wife, tells him, “I think James Quinn is a fine outline, and it’s up to you to fill it in.” Shanley, I think bravely, undertakes the return to his tumultuous past (for the nation, for himself) to try and unlock the puzzle of his earlier life. Kudos to him for not giving us pat answers — for still not truly knowing what the answers are yet, though he surely has a better grasp of the questions.

Shanley, for me, became the American Joyce the day he decided to put Prodigal Son on stage. Here is the kicker. I do not believe he set out to do that. If he had, his work would have been derivative, pretentious, blah. He just sat out to write the most searingly honest play he could. In so doing, he stumbled onto something unintended and rare: a work uniquely specific and uniquely universal. Joyce writes of Stephen, “He did not want to play. He wanted to meet in the real world the unsubstantial image which his soul so constantly beheld. He did not know where to seek it or how, but a premonition which led him on told him that this image would, without any overt act of his, encounter him.” Shapely could write the same of Jim.